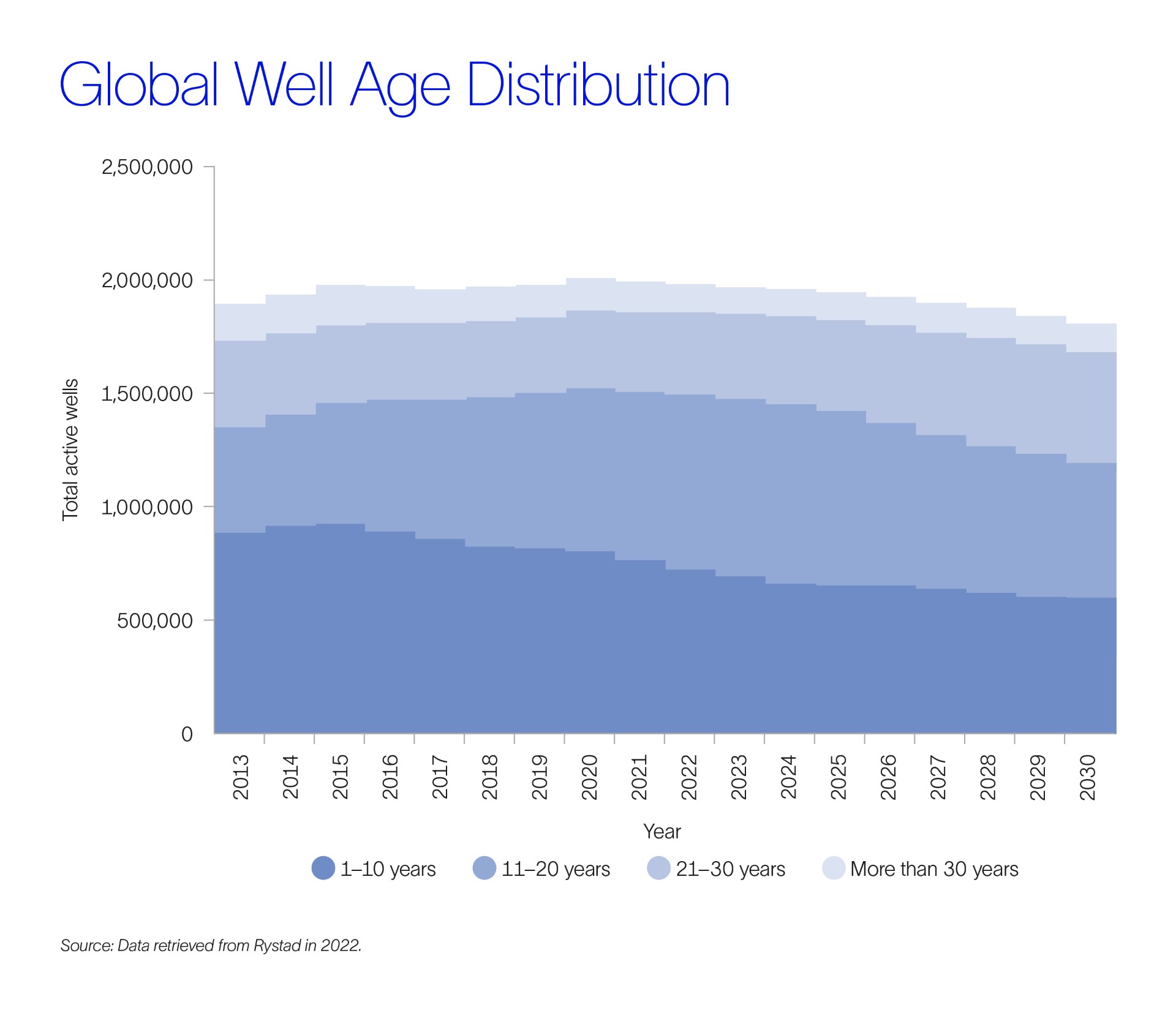

Current predictions are that the annual number of new wells drilled will not increase. It will either remain stagnant or decrease (see chart below), depending on the net-zero transition scenario modeled. Meanwhile, the global population continues to expand, with developing nations wanting access to readily available, robust energy supplies.

While significant funding is going into green energy sources, analyses performed by the International Energy Agency show that, even in a net-zero scenario, oil and gas will be significantly needed in 2050 and beyond. One of the simulations goes as far as to depict how the world would fall short of energy requirements in a net-zero scenario if we stopped investing in oil and gas starting today.

Hence the dilemma on our hands: If we are to ensure the right energy mix is available to sustain a growing population, then we must control greenhouse gas emissions holistically—and that includes within the oil and gas industry. One means of achieving this would be to ensure that we maximize, or perhaps more accurately, optimize production and recovery from the reserves that already exist today.

Can the production levels of maturing assets be maintained?

The productive fields and reservoirs of the world are maturing and, as seen in the chart above, more than two-thirds of wells will be over 10 years old by 2030. These wells will encounter production bottlenecks as they age. From a subsurface perspective, common blockers will be related to flow assurance, reservoir drive, phase conformance, well integrity, and more. Surface bottlenecks will occur, too, as the topside facility is no longer attuned to the well’s actual production.

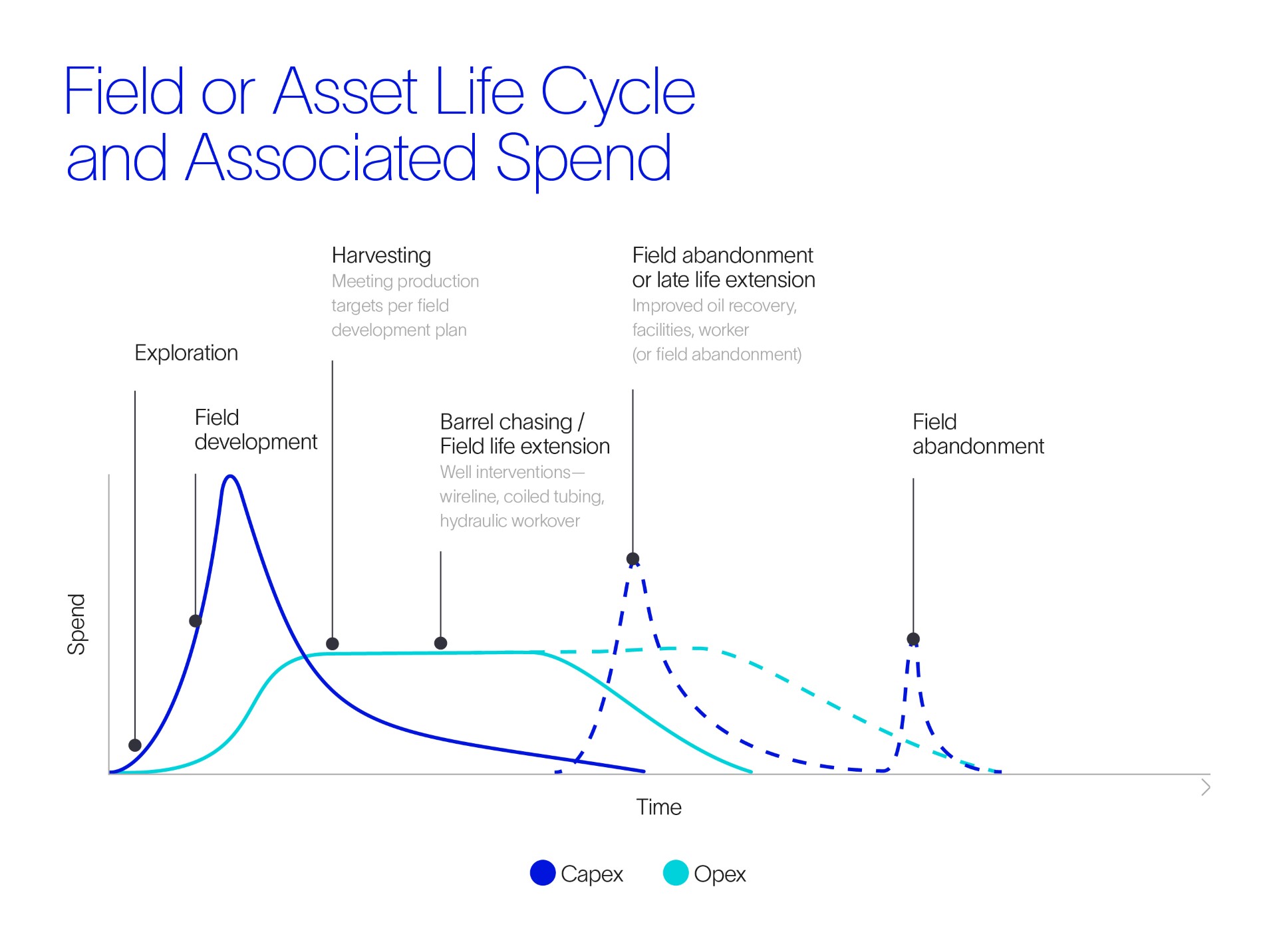

If we examine the typical life cycle of an asset, we can see how production and ultimate recovery can be optimized. Once the asset is brought online, we enter the harvest phase, with all the initial capex invested and opex now spent to operate the asset. Production will start to decline as the asset matures, but it can very well be maintained by interventions that optimize, safeguard, or even restore production. This can be achieved with small, agile intervention platforms such as slickline, electric line, or coiled tubing, ideally coupled with relevant surface production metering and handling facilities.

Secondary recovery will become more important, requiring the likes of waterflooding to support production. There will, however, come a point when the asset matures to the extent that the return becomes less effective with respect to the money spent making it. On a plot of return versus spend, this point is often referred to as “the scorpion’s tail.” An analysis then needs to be made to see whether it makes more sense to decommission the asset or to reinvest capex into field redevelopment and enhanced recovery.

Addressing the intervention challenges we face

In an SPE paper titled The Intervention Opportunity: Why the Industry Does Not Do More and How New Collaborative Workflows with Aligned Outcomes Can Change This, a couple of my peers and I identified the following headwinds:

First and foremost, asset mindset reflects the concern that intervention may be risky—that it might result in a reduction rather than increase in production should the well be adversely affected. But intervention is already challenging enough as it is. It must address a diverse range of issues, and the workflows are nonstandard in many operator organizations where the focus has always been more on reserves replacement.

Then, you have benchmark data showing that the outcomes are unpredictable, with 35% of interventions potentially not meeting their technical objectives. Such a success ratio needs to be challenged—for it is considered unacceptable in the well construction domain—but the industry lacks actionable data when it comes to interventions. Less than 10% of operations have meaningful downhole data. This is mostly due to cost and reliability concerns about more complex bottomhole assemblies on slickline, electric line, and coiled tubing. Without such data, programs cannot be tuned to real-time downhole conditions to enable a positive outcome.

Last, but not least, logistical planning for intervention is also a challenge, especially offshore. Deck space, deck loading, crane capacity, personnel-on-board limitations, and more can cause considerable issues. So much so that some operators deem this their number one issue.

Intervention operations remain an underserved tool

Benchmarking done by the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) has demonstrated that production can be increased by an average of 10% if operators invest in regular well maintenance. The number rises to as high as 19% on dry tree platforms, perhaps reflecting a greater focus on these expensive wells. To put things into perspective, achieving this on a global level would be the equivalent of bringing online two Ghawar fields overnight and approximately 10 million bbl/d.

The question then becomes: Is this economically viable? Again, NSTA benchmarking proves the case to be very much so. The average cost per barrel for production gained by intervention is about USD 12, meaning it’s of great value. It should be noted that this figure was derived from data in which 50% of intervention spend was attributed to subsea wells—a much more expensive intervention and one that accounts for just 11% of total activity. This means that in the dry tree scenario (remembering a possible 19% increase in production), the cost would be only about USD 6 per barrel.

If we review global opex and capex figures, approximately 13% is spent on well servicing, which includes both interventions and workover activity. The latter includes line items such as rig costs and tubulars and accounts for most of the spend. But even if we assumed a 50:50 split, investment in intervention activity would still be a low single-digit percentage of total spend. Is the industry missing an opportunity, and if so, why?

My experience tells me it’s more a matter of the industry realizing, under new macros, the potential of interventions. We’re simply seeing a fresh focus on production and recovery optimization, hence the claim that intervention-based production is the low-hanging fruit, providing the lowest CO2 footprint and cost production.